|

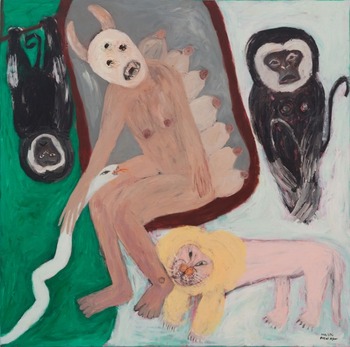

Busui Ajaw:

|

| ©Busui Ajaw |

Venue: nca | nichido contemporary art

Date: 6. 16 (fri.) – 7.29 (sat.), 2023

Gallery hours: tue. – sat. / 11:00 – 19:00 (closed on sun., mon., and on national holidays)

nca | nichido contemporary art is pleased to present Mother: Amamata, solo show by artist Busui Ajaw (b. 1986, currently based in Chiang-Rai). Marking Ajaw’s first ever solo show in Japan, the exhibition focuses on the artist’s new paintings including also a selection of recent works that have never been shown publicly, and one large-scale piece.

Busui Ajaw’s works are recognized by her paintings with expressive style with the usage of vivid colors and dramatic texture that her brush technique creates. They sometimes appear violent and psychological. However, these narratives fill me with discontent as they neglect unique aspects of her work that originates from her upbringing. It is illuminating us from a different point of view, higher from above and deeper into the distance. Ajaw belongs to the Akha, an ethnic group who originally lived in small villages in the highland area of mainland southeast Asia and southwest China. Having a semi-nomadic lifestyle, they were escapists who have been resisting the governmental power from the plain, either from the Hans, Thais, or Bamars. The Akha people have been assimilated to varying degrees into five distinct nation-states in the area. Their original belief system is a combination of animism and ancestor worship. Nowadays some have converted to Christianity and Buddhism.

Ajaw was born in Myanmar. The family escaped the political uncertainty when she was young and moved to Chiang Rai, Thailand. Although Ajaw never attends an art school, she belongs to a family of artisans. Her father, who is a sculptor, transmits his knowledge about their people through storytelling and the creation of wooden sculptures. Rather than following into her father’s footsteps, Ajaw aspired to be a painter when she was fifteen years old. She attempts to tell the story of the Akha people, which is already a challenge. Before the Christian missionary arrived in the twentieth century and introduced the Latin script, the Akhas did not have a written language. Their knowledge was conveyed through oral tradition and symbolism. Scattered throughout the highlands, their knowledge is lacking in unity. In this sense, her works are perhaps the most substantial attempt to gather and portray the Akhas’ experience in the form of visual representation.

Mother: Amamata is Ajaw’s first solo exhibition in Japan. At nca | nichido contemporary art, she is revisiting a theme that has been central to her practice. It is a continuation of her first international presentation at Singapore Biennale 2019, in which she expressed her story through the lens of an Akha woman. In Singapore, she presented a series of large paintings that told the epic of an Akhan hero. Ajaw began her narrative with a red painting of a naked woman. She wears Akha’s iconic headdresses and skulls. The painting is a depiction of Ama-ma-ta, the all-mother who gave birth to both humans and ghosts. She is a titan who was bestowed by the gods to guide the Akha people, both those who are living and the dead. Unfortunately, her passing away created a separation between the human world and the spiritual world. And those who are familiar with mythologies might be able to guess. It was the humans who outwitted the ghosts which resulted in humanity’s long-lasting curse. Nonetheless, the story of Ama-ma-ta shows that both the woman and the mother play a central role in the traditional Akha culture.

In this exhibition, Ajaw is revisiting the figure of Ama-ma-ta from her experience as a mother. The paintings in the exhibition were painted while she was raising her firstborn. They resulted from a contemplation on reality as she experienced it. From her distinctive standpoint, she is not only able to tell the story about her tradition but she also underlines the oppression her people have suffered from, as the modern patriarchal societies also extend their reach to the mountains. While these works come from a distanced upland, they are also coming from below; from the undercommon of Thai society. Ajaw also brings the ghosts back into the painting. In her own words, humans and ghosts lived together in Ama-ma-ta time for a reason. Humans’ mind is pliable, and we tend to deny that characteristic of ourselves. Thus, humans create their counterpart in the darkness. In ghosts, we see our own weakness, which causes and endless circle of discrimination and exploitation. Attempting to paint without sugarcoating the subject, Ajaw gives the spotlight to those who have been hiding in the shadow: women who live in a state of precarity. They might be stateless and homeless. They might be prostitutes or single mothers. They might be all the above. She attempts to return to the all-mother bringing forth the primordial worldview that we have long forgotten so she could cast the light on those who need it the most. Thus, we could face the ghosts, and the circle could be broken.

Vipash Purichanont (Independent curator)